In 2016, The Sentry’s 2-year investigation ‘In South Sudan, war crimes shouldn’t pay’ revealed networks fueling one of the world’s deadliest conflict zones implicating President Salva Kiir and former Vice President Riek Machar, international banks, arms dealers, multinational oil and mining companies.

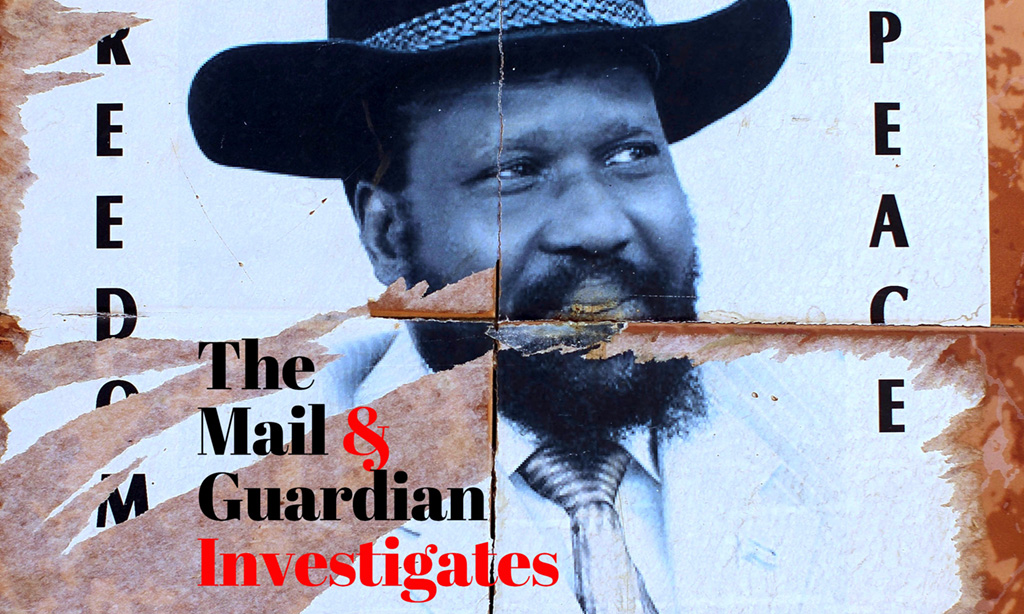

A new report by The Mail & Guardian titled: How South Sudan’s elite looted its foreign reserves confirms how family and friends of top government officials benefited from letters of credit scam. Simon Allison writes as an iintroduction to the report:

In South Sudan, we know who is dying. At least 50 000 people, mostly civilians, in nearly four years of fighting. That figure is probably a gross underestimate. Another four million – a third of the population – have been forcibly displaced from their homes, fleeing to squalid refugee camps in neighbouring countries or trying to make a new life in dangerous, unfamiliar conditions somewhere else in the country. Families have been torn asunder, livelihoods abandoned, future generations sacrificed in the near-complete absence of education and basic healthcare.

Here’s an extract from Simona Foltyn’s report:

At that time, South Sudan was well into the second year of a bloody civil war — a war that is yet to be resolved. Oil revenues had declined by a third, and the country’s dwindling foreign reserves had become its most sought-after commodity — especially for those in power. In order to address the country’s acute shortage of hard currency, the Bank of South Sudan earmarked $993-million in oil revenues between 2012 and 2015 to import vital goods like medicine and food. Ministries allocated the hard currency to selected traders at a preferential exchange rate through letters of credit (LCs), a documentary credit facility commonly used to facilitate international trade. But instead of helping South Sudan’s impoverished population, the LCs became one of the biggest corruption scandals in South Sudan’s short but troubled history…

Another report detailling the ramping corruption in South Sudan. You can read it on this page.